This is a mural of King Niall (Nıall Caılle, Niall of the Callan) and Queen Macha. Niall was high king of Ireland (in competition with Fedelmıd of Munster WP) who held off the Vikings in the late 800s (WP) and died in 846 by drowning in the Callan river. Macha is a much earlier and mythological queen, and gives her name to the town: Ard Mhacha.

The central figures reproduce paintings by Jim Fitzpatrick (Visual History). The Niall figure comes from Nemed The Great but the Macha figure comes from a label Fitzpatrick produced in 1988 for Rosc “mead”, even though Macha (one of them, at least) was the wife of Nemed and there is a female figure in Nemed The Great.

Below the planets and stars, St Patrick’s (Catholic) Cathedral is on the left (WP) and St Patrick’s (CofI) Cathedral is on the right (WP).

In the border, clockwise from left to right, we see: the Tandragee Idol (WP), Naomh Bríd/St Brigid’s, St Patrick preaching the trinity, Irish dancing, Gaelic football, Armagh Harps, “Ard Mhacha”, the Armagh county crest in colour in the apex (Club & County), “Armagh”, Na Pıarsaıgh Óga, hurling/camogie, Cú Chulaınn’s, mummers (perhaps specifically the Armagh Rhymers), Jonathan Swift, a steam locomotive (perhaps representing the Armagh rail disaster of 1889, in which 80 people died WP); a vintage image of Callan Street is depicted along the bottom (History Armagh).

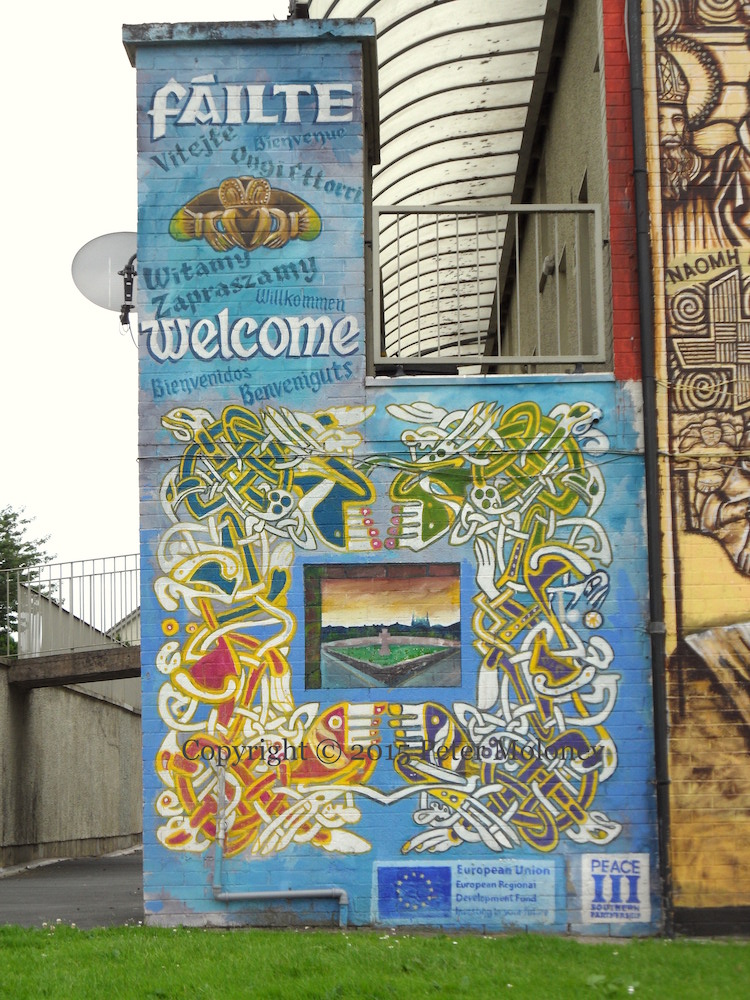

The side-wall features the word “welcome” in many languages, and Celtic knot-work surrounding an image of the Celtic Cross below St Patrick’s, perhaps inspired by this 1903 photograph (Flickr).

Painted by a crew of Belfast artists – Danny D and Mark Ervine, along with Lucas Quigley, Marty Lyons, Micky Doherty – organised by the Callan Street Residents’ Association, with funding from the European Union’s Peace III initiative.

Culdee Crescent/Callan Street, Armagh

Click image to enlarge

Copyright © 2015 Peter Moloney

M12742 M12743 M12744 M12745 M12746